Follow Us

Options Trading Guide: Everything Beginners Need to Know

Table of Contents

Why Learn Options Trading?

Options trading can seem intimidating at first glance. Charts with strange letters, expiration dates, and terms like Greeks or implied volatility often make beginners think, “This is too complicated for me.”

But in reality, options are not as mysterious as they look. Once you understand the core mechanics, they become one of the most powerful, flexible tools in the world of investing.

So why are options so appealing, especially for beginners?

- Leverage & Flexibility: With a small amount of capital, you can control far more stock than if you purchased it outright. This leverage can amplify returns (though it can also amplify losses, which we will cover in detail later).

- Multiple Uses: Options aren’t just for speculation. They can be used to generate income (covered calls), protect your portfolio from losses (hedging with puts), or even buy stocks at a discount (cash secured puts).

- Defined Risk (for buyers): When you buy an option, your maximum loss is limited to the price (premium) you paid for the contract. Compare that to shorting a stock, where losses can be unlimited.

Think of this guide as your crash course, your A to Z roadmap for understanding how options work, how they are priced, the risks involved, and how to start safely.

By the end, you will have the confidence to place your first practice trade and know exactly what’s happening behind the scenes.

If you are new to the markets, it’s essential to first learn the basics of stock trading. Check out our complete guide on how to start trading stocks as a beginner before diving into options.

Key Takeaways: Options Trading for Beginners

By the end of this beginner’s guide to options trading, you will understand:

- Options Are Contracts, Not Stocks: An option gives you rights, not ownership. You will learn what this means and why it matters.

- Calls & Puts Simplified: The two building blocks of options: buying vs selling, bullish vs. bearish, explained with easy analogies.

- How Options Are Priced: You will see how time, volatility, and stock movement influence the premium.

- Risks You Must Respect: From time decay to assignment risk, we will cover the biggest pitfalls beginners face.

- Safe Starter Strategies: Covered calls, cash-secured puts, and vertical spreads, practical ways to trade options without blowing up your account.

What Is an Options Contract?

At its core, an option is a contract. It gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a stock at a predetermined price within a certain time frame.

That last phrase, “not the obligation” is the heart of why options are so powerful. Unlike owning stock outright, you are not locked in. You can choose to act or walk away depending on what’s best for you.

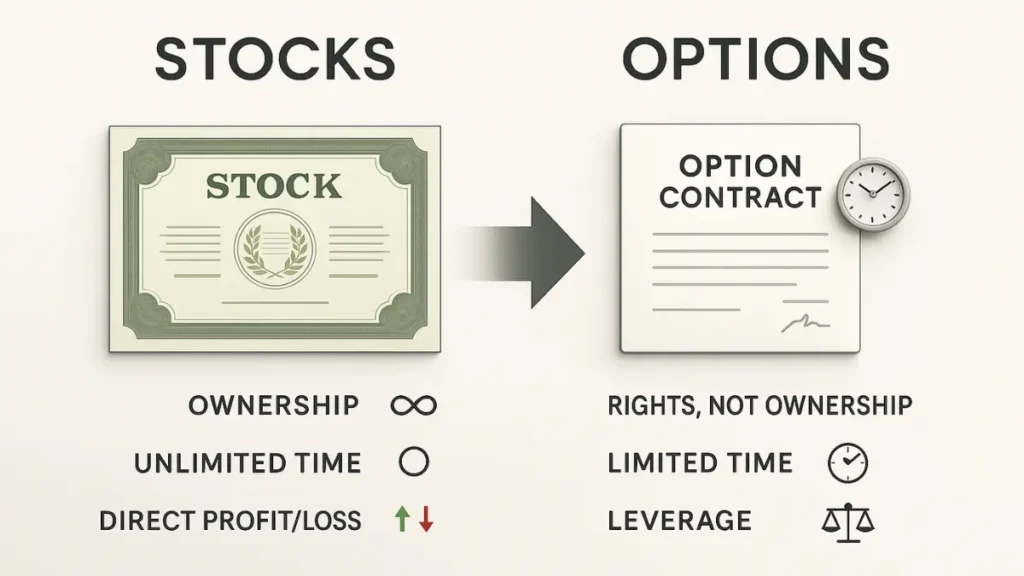

Options vs Stocks: Key Differences

- Owning Stock:

If you buy 100 shares of XYZ, you own a piece of the company. Your profit or loss is directly tied to how XYZ stock price moves.

If it goes up $10, you make $1,000 (100 × $10). If it goes down $10, you lose $1,000. - Owning an Option:

If you buy a call option on XYZ with a strike price of $150, you have the right to buy 100 shares of XYZ at $150, no matter where the stock trades in the future (until expiration).

If XYZ jumps to $170, your option becomes extremely valuable because you can still buy at $150. If XYZ drops to $140, you don’t have to buy, your loss is limited to the option’s cost (the premium).

This flexibility is what makes options attractive. You can control the same 100 shares of XYZ for a fraction of the price. Instead of needing $15,000 to buy 100 shares outright, you might pay $500–$1,000 for an option contract.

A Simple Analogy: Options as a Concert Ticket

Imagine you want to see Taylor Swift in concert. Tickets cost $500 today, but you are not sure if you will be available on the concert date.

- So, you strike a deal with a friend: for $50, they will reserve you the right to buy a ticket from them for $500 anytime in the next three months.

- If demand for tickets skyrockets to $1,000, you can still buy from your friend at $500, an instant bargain.

- If you can’t go, or tickets stay at $500, you lose only the $50 fee.

That $50 is the option premium, and the deal itself is the option contract. You had the right, not the obligation, to buy the ticket.

Why This Difference Matters:

Options free you from the all or nothing commitment of owning stock. You are paying for flexibility and leverage.

But there is a catch:

Unlike stocks, options expire. If you hold a stock for 10 years, you still own it.

If you hold an option for a long time (not possible in practice, since options usually last weeks or months), it would eventually expire worthless unless acted upon.

This ticking clock changes everything. It introduces risks like time decay and expiration deadlines.

Now that you know what an option is, let’s move to the next building block: Types of Options (Calls & Puts).

Call Options vs Put Options (Types of Options)

Every option boils down to one of two basic types:

- Call Options – The right to buy.

- Put Options – The right to sell.

Once you understand these, every other strategy, no matter how advanced, is just a combination or variation of calls and puts.

Call Options: The Right to Buy

A call option gives you the right (but not the obligation) to buy a stock at a specific price (strike price) before the expiration date.

When do traders buy calls?

- When they think a stock will go up.

For Example:

Suppose stock named XYZ is trading at $400. You buy a call option with a strike price of $410, expiring in one month, for a premium of $5 per share ($500 total since 1 contract = 100 shares).

Because the strike ($410) is above the stock price ($400), this option is out of the money at entry. That means the entire $5 premium is time value, not intrinsic value.

- If the stock rises to $450 by expiration, the call option’s intrinsic value is $40 per share ($450 – $410). That makes the contract worth $4,000.

- Subtract your initial cost ($500), and your net profit is $3,500, a huge return.

- If the stock stays below $410, the option expires worthless, and your loss is limited to the $500 premium.

A call option is like putting a deposit on a house. For a small upfront fee, you secure the right to buy the property at today’s price.

If the house value skyrockets, you have locked in a bargain. If the market crashes, you can walk away and only lose your deposit.

Put Options: The Right to Sell

A put option gives you the right (but not the obligation) to sell a stock at a specific price before expiration.

When do traders buy puts?

- When they think a stock will go down.

- Or, when they want insurance against losses in stocks they already own.

For Example:

Suppose ABC is trading at $250. You buy a put option with a strike price of $240, expiring in one month, for a premium of $4 per share ($400 total).

- If ABC falls to $210, your option is worth at least $30 per share ($3,000 total value). That’s protection if you already owned 100 shares.

- If ABC rises above $240, your option expires worthless, and you lose the $400 premium.

A put option works like insurance. Think about car insurance, you pay a premium each month.

If your car crashes (the stock price falls), the insurance pays out. If your car is fine (stock price stable or rising), the insurance expires unused, but you had peace of mind.

Common Use Cases for Calls & Puts

- Speculation: Betting on stock moves (buying calls for bullish bets, puts for bearish).

- Hedging: Protecting your portfolio (buying puts on stocks you already own).

- Income Generation: Selling covered calls or cash-secured puts to earn premiums.

Buying vs Selling Options: Risk, Reward, and When to Use

Now that you know what calls and puts are, the next step is to understand the difference between buying and selling them.

- Buyers pay a premium and hold a right, not an obligation.

- Sellers collect a premium but take on an obligation if the buyer exercises.

This difference changes everything: your profit potential, risk, and role in the market.

1. Call Buying – Bullish Bet with Limited Risk

What it means: You pay a premium to gain the right to buy the stock at the strike price.

Directional Bias: Bullish (you expect the stock to rise).

Max Profit: Unlimited, since a stock’s price can keep rising.

Max Loss: The premium paid.

Example:

Apple (AAPL) trades at $150. You buy a $160 call for $5 ($500 total).

- If AAPL rises to $180 by expiry, your option has $20 of intrinsic value = $2,000. Profit = $1,500.

- If AAPL stays below $160, the option expires worthless. Loss = $500.

Buying calls is a leveraged way to bet on rising prices, with risk capped at the premium.

2. Call Selling – Income with High Risk

What it means: You collect a premium by giving someone else the right to buy the stock from you.

Directional Bias: Neutral to slightly bearish (you expect the stock to stay below the strike).

Max Profit: Limited to the premium collected.

Max Loss: Potentially unlimited if the stock rises sharply.

Example:

You sell a $160 call on AAPL for $5, collecting $500.

- If AAPL stays below $160, the call expires worthless, and you keep the $500.

- If AAPL rises to $200, you’re forced to sell 100 shares at $160 (a huge loss if you don’t own them).

Call selling is very risky if “naked” (without owning shares). The safer version is the covered call strategy, selling calls against stock you already own.

3. Put Buying – Bearish Bet or Portfolio Insurance

What it means: You pay a premium to gain the right to sell stock at the strike price.

Directional Bias: Bearish (you expect the stock to fall).

Max Profit: Large, limited only by the stock falling to zero.

Max Loss: The premium paid.

Example:

Tesla (TSLA) trades at $250. You buy a $230 put for $4 ($400 total).

- If TSLA drops to $200, your put is worth $30 = $3,000. Profit = $2,600.

- If TSLA stays above $230, the option expires worthless. Loss = $400.

Put buying is a simple way to profit from a falling stock or to hedge existing stock you own.

4. Put Selling – Income with Downside Risk

What it means: You collect a premium by giving someone else the right to sell stock to you.

Directional Bias: Neutral to slightly bullish (you expect the stock to stay above the strike).

Max Profit: Limited to the premium collected.

Max Loss: Large if the stock collapses (since you may be forced to buy at the strike).

Example:

You sell a $230 put on TSLA for $5, collecting $500.

- If TSLA stays above $230, the put expires worthless, and you keep $500.

- If TSLA drops to $150, you must buy 100 shares at $230 = $23,000, even though they’re worth $15,000 (a $7,500+ loss).

Put selling is risky if naked, but safer as a cash secured put, where you set aside cash to buy the shares at your chosen strike.

Quick Comparison Table: Buy vs Sell (Calls & Puts)

| Strategy | Directional Bias | Max Profit | Max Loss | Safer Beginner Version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Call Buying | Bullish | Unlimited | Premium paid | Basic speculation |

| Call Selling | Neutral/Bearish | Premium only | Unlimited (naked) | Covered Call |

| Put Buying | Bearish | Large (to 0) | Premium paid | Hedge against stock falls |

| Put Selling | Neutral/Bullish | Premium only | Large (if stock crashes) | Cash-Secured Put |

Takeaway for Beginners:

- Buy options if you want defined risk and unlimited upside/downside potential.

- Sell options only in safer forms (covered calls, cash-secured puts). Naked selling is too risky for beginners.

Related Post:

How to Start Forex Trading as a Beginner

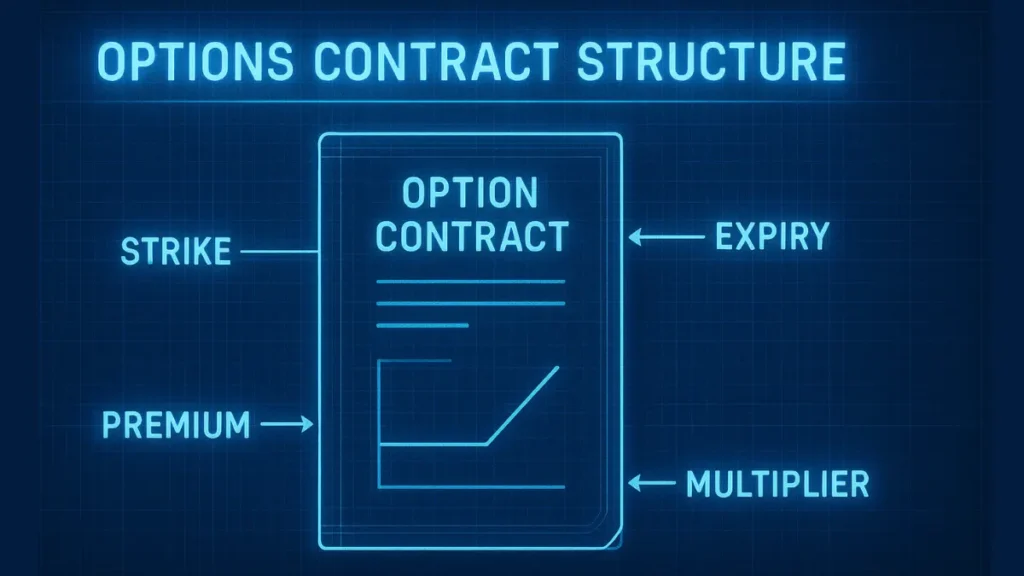

Options Contract Basics: Strike, Expiration, Premium, Multiplier

Every option, no matter how complex it looks on your trading screen, is built around a few simple components. Think of these as the DNA of an option contract.

1. Strike Price

The strike price is the price at which you can buy (call) or sell (put) the underlying stock.

- For calls: It’s the price you can buy the stock.

- For puts: It’s the price you can sell the stock.

Example:

If you own a call option with a strike price of $100, and the stock rises to $120, you have the right to buy at $100. That’s a built in discount of $20 per share.

Why it matters:

The strike price determines whether your option is in the money (ITM), at the money (ATM), or out of the money (OTM).

2. Expiration Date

Options aren’t forever. Each contract has an expiration date, after which it ceases to exist (rules below are as per U.S. markets):

- Weekly options: Expire every Friday.

- Monthly options: Expire on the third Friday of the month.

Example:

If you buy an Apple call option expiring in 30 days, you must decide before that deadline whether to sell it, exercise it, or let it expire worthless.

Why it matters:

The expiration date puts a time limit on your trade. Unlike stocks, which you can hold forever, options are like a ticking clock.

3. Premium (The Option’s Price)

The premium is the price you pay (as a buyer) or receive (as a seller) for the option contract.

- Determined by intrinsic value (real value) + extrinsic value (time and volatility value).

- Influenced by stock price, strike price, volatility, and time until expiration.

Example:

If a Microsoft call option has a strike price of $300 and trades for a $7 premium, you pay $700 total for one contract (since 1 contract = 100 shares).

Why it matters:

Premiums are your upfront cost and also your maximum risk when you are buying options.

4. Contract Multiplier

In U.S. stock options, 1 contract controls 100 shares of stock. This is known as the multiplier.

Example:

If you buy one Amazon call option at a $5 premium, your total cost is $500 (5 × 100). If the option rises to $15, your profit is $1,000 (gain of $10 × 100).

Why it matters:

The multiplier magnifies both profits and losses. It’s the reason options can provide massive leverage compared to buying stocks outright.

Putting It All Together:

Let’s say you buy 1 call option on Apple (AAPL):

- Strike Price: $150

- Expiration: 30 days

- Premium: $3.00

- Multiplier: 100

Your cost = $300 (3 × 100).

- If AAPL rises to $160, your option has $10 of intrinsic value → worth $1,000. Profit = $700.

- If AAPL stays at $150 or below, your option expires worthless. Loss = $300 (your premium).

This simple structure, strike, expiration, premium, multiplier is the foundation for everything else you will learn about options.

American vs European Options

Not all options are created equal. The terms “American” and “European” don’t refer to geography but to when the option can be exercised.

Understanding this distinction is crucial because it affects how flexible your contract is.

American Options

- Definition: Can be exercised any time before the expiration date.

- Most U.S. stock options fall into this category.

Example: You buy a call option on Apple with a strike price of $150 expiring in 30 days.

- If Apple jumps to $170 just 10 days into your contract, you can exercise immediately and buy the shares at $150.

- Or you can hold the option longer, hoping for further gains.

Why it matters: American options give you maximum flexibility. You are not forced to wait until expiration to act.

European Options

- Definition: Can be exercised only on the expiration date.

- In India, all index and stock options (like Nifty 50 and any stock) are European-style, meaning they can only be exercised on the expiration date.

Example: You buy a Nifty 50 call option with a strike price of 22,000, expiring in one month.

- Even if Nifty rises to 22,500 two weeks later, you cannot exercise early. You must wait until expiration.

- On expiration day, if Nifty is above 22,000, the option is exercised. If not, it expires worthless.

Why it matters:

- Index options (like Nifty 50 and Bank Nifty) are cash-settled; profits or losses are adjusted in your trading account.

- Stock options (like Reliance, Infosys, HDFC Bank) are physically settled; if you hold the contract till expiry and it’s in the money, you must actually buy or sell the underlying shares in lots of the contract size.

For beginners, this means you can always square off (sell your option) before expiry, but if you hold till the end, be prepared for cash settlement in indexes or share delivery in stocks.

Cash vs Physical Settled Options

When an option is exercised (by the buyer) or assigned (to the seller), what actually happens?

Do you get shares, or just cash? The answer depends on whether the option is physically settled or cash-settled.

Physically Settled Options

- Definition: Settlement involves actual shares of stock changing hands.

- Applies to most U.S. stock options.

Example:

You buy 1 call option on Apple (AAPL) with a strike of $150. At expiration, AAPL is $160.

- If you exercise, you buy 100 shares of AAPL at $150 (cost = $15,000).

- Immediately, your shares are worth $16,000 in the market. Profit = $1,000 (minus premium paid).

For sellers: If you sold that same call, and it’s exercised, you must deliver 100 shares of AAPL at $150, no matter the market price. This is what traders call “being assigned.”

Takeaway: Stock options usually require you to be prepared for delivery of 100 shares per contract.

Cash Settled Options

- Definition: Settlement happens in cash, not shares.

- Common with index options.

Example:

You buy an S&P 500 index call with a strike of 4,000. At expiration, the index is 4,100.

- You don’t get index shares (impossible anyway). Instead, you receive the cash difference:

- 100-point gain × 100 multiplier = $10,000 profit.

For sellers: If you sold that call, you owe $10,000 cash.

Takeaway: Cash settled options remove the logistics of transferring shares. Instead, you just settle the profit/loss in your account.

Next up, we will break down one of the most important concepts for beginners: In the Money (ITM), At the Money (ATM), and Out of the Money (OTM).

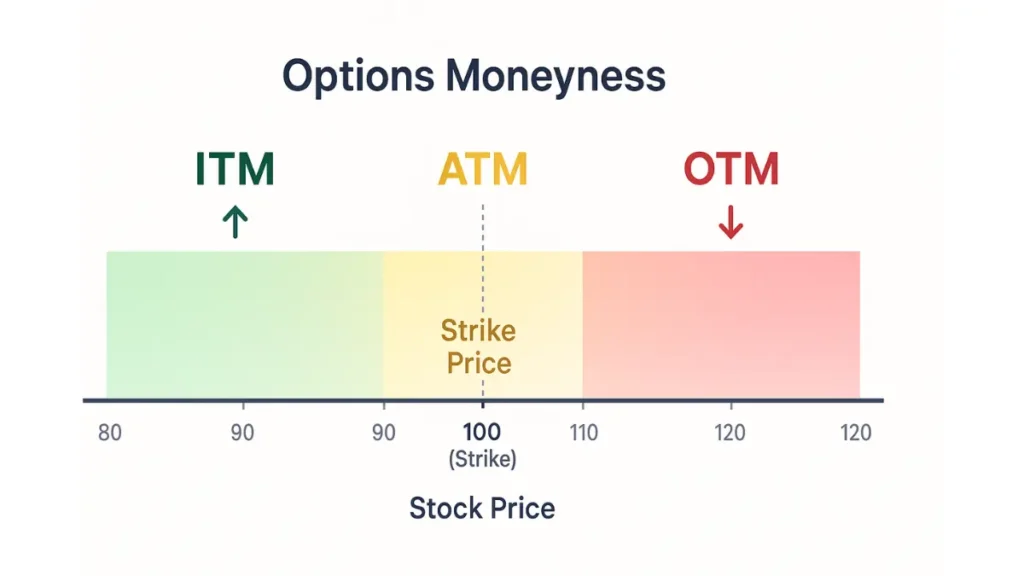

In the Money (ITM), At the Money (ATM), Out of the Money (OTM)

Options have different “moneyness” levels depending on the relationship between the stock price and the strike price. This is critical because it affects value, cost, and risk.

In the Money (ITM)

- A call option is ITM if the stock price is above the strike price.

- A put option is ITM if the stock price is below the strike price.

Example:

- Stock = $55

- Call option with strike = $50 → ITM (worth at least $5).

- Put option with strike = $60 → ITM (worth at least $5).

Why ITM matters: ITM options have intrinsic value (real, guaranteed value). They are more expensive but less risky than OTM options.

At the Money (ATM)

- A call or put is ATM when the stock price is very close to the strike price.

Example:

- Stock = $100

- Call or put with strike = $100/$101 → ATM.

Why ATM matters: ATM options are pure bets on future movement. They have no intrinsic value, only extrinsic (time + volatility) value.

Out of the Money (OTM)

- A call option is OTM if the stock price is below the strike price.

- A put option is OTM if the stock price is above the strike price.

Example:

- Stock = $90

- Call option with strike = $100 → OTM (worth $0 if expired today).

- Put option with strike = $80 → OTM (worth $0 if expired today).

Why OTM matters: OTM options are cheaper but riskier. They often expire worthless because the stock never moves enough to make them valuable.

Why ITM Options Cost More than OTM

- ITM = includes real value (intrinsic).

- OTM = only hope value (extrinsic).

Traders pay more for ITM options because they already have guaranteed worth. OTM options are cheaper, but they are like lottery tickets, big upside if the stock moves, but high chance of total loss.

Options Expiration: What Happens Before & At Expiry

One of the biggest beginner misconceptions about options is that you must hold until expiration and either exercise the option or lose it. In reality, most traders do something very different.

Most Traders Close Before Expiration (Here’s Why)

Studies show that the majority of options contracts are closed out before expiration. Why? Because traders don’t actually want the shares, they want to profit from the change in the option’s price.

You can always sell the option back into the market before expiration, just like you’d sell a stock. This is called “closing the position.”

Expiration Outcomes: Exercise, Assignment, or Expire

If you do hold until expiration, there are only three possible outcomes:

1. Exercise (by the buyer):

If you hold a call that’s in the money, you can buy 100 shares at the strike price.

If you hold a put that’s in the money, you can sell 100 shares at the strike price.

2. Assignment (to the seller):

If you sold the option, you may be forced to buy (puts) or sell (calls) 100 shares if the buyer exercises.

This is why sellers face higher risks, they may be assigned at the worst possible time.

3. Expire Worthless (for OTM options):

If your option is out of the money, it simply disappears. You lose only the premium you paid.

Example: You bought a $100 call on Microsoft, but the stock is $95 at expiration. The option expires worthless.

Why Beginners Should Close Positions Early

- Flexibility: You can lock in profits before they disappear.

- Risk Reduction: Holding to expiration can expose you to last-minute volatility or unexpected assignment.

- Liquidity: The option market allows you to trade in and out easily, use it!

How Options Are Priced (The Premium Breakdown)

Every option has a premium; the price you pay as a buyer or receive as a seller. But where does that number come from?

The premium has two main components:

- Intrinsic Value – the “real” value.

- Extrinsic Value – the “hope and time” value.

1. Intrinsic Value

Definition: The value an option would have if it were exercised today.

- For calls: Stock price − Strike price (if positive).

- For puts: Strike price − Stock price (if positive).

Example:

Apple stock = $160

- $150 call option = $10 intrinsic value.

- $170 call option = $0 intrinsic value (OTM).

Intrinsic value is guaranteed value, it can’t be negative.

Extrinsic Value (Time & Volatility Value)

This is everything above intrinsic value. It reflects time left and uncertainty about the future.

Time Value (Theta): Options with more time until expiration are more expensive because the stock has more time to move. Think of it like renting a house; the longer you rent, the more you pay.

Volatility Value (Vega): The higher the expected volatility, the more expensive the option. Why? Because big swings mean bigger potential payouts.

Example:

Two call options on Tesla with the same strike:

- 1 week until expiration = $5.

- 3 months until expiration = $15.

Same strike, but more time = higher premium.

The Engine of Price: Implied Volatility (IV)

Implied Volatility is the market’s forecast of how much the stock might move.

- High IV = Expensive Options. (Market expects big swings like before earnings reports.)

- Low IV = Cheap Options. (Market expects calm trading.)

Beginners often overpay for options before big events, only to watch them collapse in value afterward. This collapse is called volatility crush.

Time Decay (Theta) – The Melting Ice Cube

Every day, an option loses a bit of value if everything else stays the same. This is time decay.

The closer you get to expiration, the faster the decay. It’s like an ice cube melting; slow at first, then rapidly as it shrinks.

A 30-day call might lose $5 of value slowly over 20 days, but then $15 of value in the last 10 days as expiration approaches.

For option buyers, time decay is the enemy. For option sellers, it’s an advantage.

Option premiums = Intrinsic Value + Extrinsic Value.

- Intrinsic = Real, guaranteed worth.

- Extrinsic = Time left + volatility expectations.

- High volatility & longer expiration = expensive options.

- Time decay erodes extrinsic value daily.

Options Greeks Explained: Delta, Theta, Vega, Gamma

If options pricing feels like a puzzle, the Greeks are the pieces that explain how an option’s price reacts to different factors.

They may sound pro at first, but each one answers a specific, practical question every trader has.

Delta – Sensitivity to Stock Price

Question it answers: “How much will the option move if the stock moves $1?”

- Call options: Delta ranges from 0 to +1.

- Put options: Delta ranges from 0 to -1.

Example:

- A call option with Delta = 0.50 means if the stock rises $1, the option’s premium rises about $0.50.

- A put with Delta = -0.40 means if the stock drops $1, the option’s premium rises $0.40.

Theta – Sensitivity to Time (Time Decay)

Question it answers: “How much value will this option lose each day, just from time passing?”

- Theta is almost always negative for buyers.

- If an option has Theta = -0.05, you lose $5 per day per contract, even if the stock doesn’t move.

Example:

- You buy a Tesla call with Theta = -0.10. That’s a $10 daily loss (since 1 contract = 100 shares).

- After 10 days of no stock movement, your option is $100 cheaper, just because of time decay.

Takeaway: Theta works against buyers, for sellers.

Vega – Sensitivity to Volatility

Question it answers: “How much will this option’s price change if implied volatility changes by 1%?”

- Options with high Vega are more sensitive to volatility shifts.

- Long-dated options tend to have higher Vega than short-dated options.

Example:

- A call option with Vega = 0.12 means if IV rises 1%, the premium increases by $12.

- If IV drops 1%, you lose $12 in value.

This is why traders can lose money even if the stock moves in their favor, if volatility collapses (vol crush), the option price can still fall.

Gamma – Sensitivity of Delta

Question it answers: “How much will Delta change if the stock moves $1?”

While Delta tells you how much the option price moves with the stock, Gamma tells you how fast Delta itself will change.

High Gamma means Delta can shift quickly; your option becomes more sensitive to stock price moves. Gamma is usually highest for at-the-money (ATM) options close to expiration.

Why it matters for beginners: Gamma shows you how explosive an option can become as the stock moves. It explains why near-expiry ATM options can suddenly swing wildly in value.

Why Beginners Should Care About the Greeks

- Delta = Your directional bet (how much the option moves with the stock).

- Theta = The cost of waiting (time decay).

- Vega = How volatility can blindside you (IV shifts).

- Gamma = The “accelerator” for Delta (how quickly sensitivity ramps up).

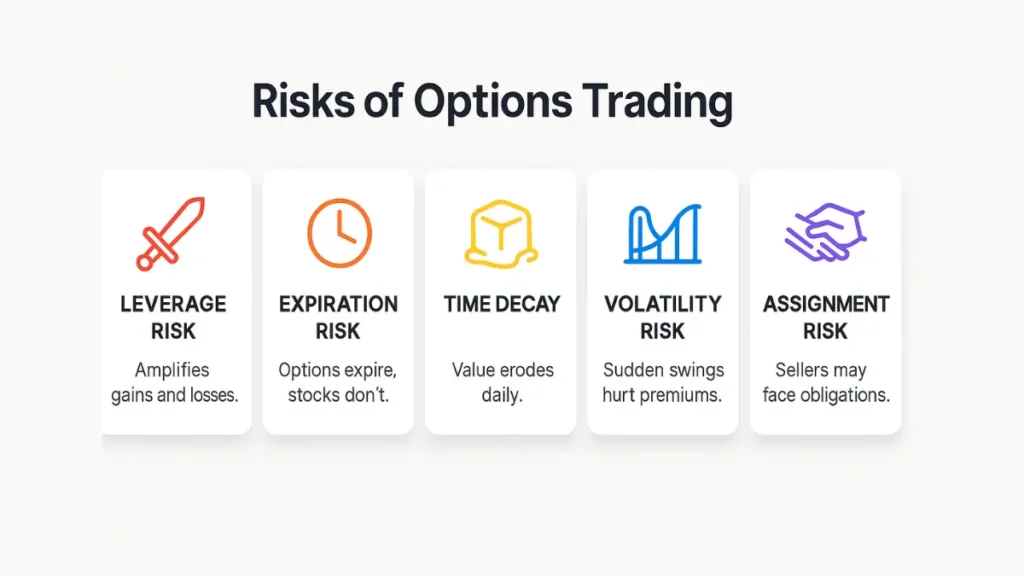

The Real Risks of Options Trading

Options can be incredibly rewarding, but they’re not a free lunch. Many beginners dive in, lured by stories of massive profits, without realizing the hidden traps.

To trade options successfully, you must respect the risks as much as the rewards.

Here are the five key risks every beginner must understand:

1. Leverage Risk (Double-Edged Sword)

Leverage is what makes options attractive, you can control 100 shares of stock for a fraction of the cost. But leverage cuts both ways.

For Example:

Buying 100 shares of Microsoft at $300 costs $30,000. If the stock rises 10% to $330, you gain $3,000 (10%).

Buying a call option for $500 gives you similar exposure. If the stock rises 10%, your option might jump to $2,000, a 300% gain.

But if the stock falls just 5%, your entire $500 could vanish.

Takeaway: Small stock moves can lead to massive percentage gains or a 100% loss of your premium.

2. Expiration Risk (Limited Lifespan)

Stocks can be held indefinitely. Options can’t. Every option comes with a deadline.

If your thesis doesn’t play out before expiration, the option may expire worthless even if you were “right” long term.

Timing becomes just as important as direction.

Takeaway: You can be right about the stock and still lose money if you’re wrong about the timing.

3. Time Decay Risk (Theta)

Every day, your option loses value if all else stays the same. This is the slow bleed that catches beginners off guard.

Example:

You buy a call on Tesla for $1,000 with 30 days left. Even if Tesla’s price doesn’t move, the option could decay to $500 in just two weeks.

Takeaway: Time is your enemy as a buyer. It’s a built-in cost that never stops.

4. Volatility Risk (IV Changes)

Options are priced heavily on implied volatility (IV). High IV = expensive options.

Example:

You buy a Netflix call before earnings for $1,500. Netflix beats earnings, stock rises $20 but implied volatility collapses after the announcement. Instead of making money, your option drops to $800.

Takeaway: You can lose money even if you guessed the stock direction right, simply because volatility collapsed.

5. Assignment Risk (For Sellers)

If you sell an option, you are on the hook if the buyer exercises. This can mean:

- Selling 100 shares you own (covered call).

- Buying 100 shares you may not want (cash-secured put).

- Or, in the case of naked options, unlimited risk being forced to sell shares you don’t even own.

Takeaway: Selling naked options is not for beginners. Always trade with protection (covered calls, cash-secured puts, or spreads).

Best Options Strategies for Beginners

If you are new to options, you should avoid complex strategies and high-risk trades. Instead, start with conservative, risk-defined strategies that allow you to learn the mechanics without blowing up your account.

Here are the three best starter strategies for beginners:

1. Covered Calls (Earn Income from Stocks You Already Own)

What it is:

- You sell a call option on a stock you already own (at least 100 shares).

- You collect a premium in exchange for giving someone else the right to buy your shares at a higher price.

Example:

- You own 100 shares of Apple at $150.

- You sell a $160 call option for $3 ($300).

- If Apple stays below $160, you keep your shares + the $300 premium (income).

- If Apple rises above $160, your shares may be sold at $160. You still keep the $300 premium + the $10 gain per share.

Why it’s beginner-friendly:

- You’re generating income from stock you already own.

- Risk is limited to owning the stock (something you wanted anyway).

2. Cash Secured Puts (Get Paid to Wait for Stocks You Want)

What it is:

- You sell a put option on a stock you want to buy, while holding enough cash to purchase 100 shares.

- If the stock falls, you may be forced to buy at the strike price, but you get to keep the premium.

Example:

- Tesla trades at $250, but you’d like to buy at $230.

- You sell a $230 put option for $5 ($500).

- If Tesla stays above $230, you keep $500, and nothing happens.

- If Tesla drops to $230, you’re assigned 100 shares at $230, but you effectively bought them for $225 (strike minus premium).

Why it’s beginner-friendly:

- You are either getting paid to wait or buying a stock you already want at a discount.

3. Vertical Spreads (Define Your Risk from the Start)

What it is:

- You buy one option and sell another at a different strike price, same expiration.

- This limits both your profit and your loss.

Example (Bull Call Spread):

- Buy a $50 call for $3.

- Sell a $55 call for $1.

- Net cost = $2 ($200 total).

- If the stock rises above $55, your profit = $300 (max).

- If the stock stays below $50, your loss = $200 (max).

Why it’s beginner-friendly:

- You always know your maximum loss and maximum gain.

- Cheaper to trade than buying calls or puts outright.

What Beginners Should Avoid:

- Naked Options Selling: Unlimited risk. One bad trade can wipe out your account.

- Complicated Multi-Leg Strategies (Iron Condors, Butterflies, etc.): These require advanced knowledge of volatility and Greeks.

Stick to covered calls, cash secured puts, and vertical spreads until you’re fully comfortable.

How to Start Trading Options: Broker, Approval, Orders & Costs

Before you can place your first options trade, you need the right tools and approvals in place. This step is often overlooked, but it makes the difference between smooth, low-cost trading and constant frustration.

Choosing the Right Broker

Not all brokers are created equal for options trading. Here’s what to look for:

- Low Commissions: Many brokers now offer 0 commissions for stock trading, but some still charge per-option contract fees. Compare carefully.

- User-Friendly Platform: As a beginner, you want a clear, intuitive interface not something overloaded with advanced tools.

- Options-Specific Features: Look for real-time option chains, Greeks data, risk analysis, and good mobile functionality.

- Education & Paper Trading: The best brokers include learning resources and simulated trading.

Don’t choose a broker only for “free trades.” Pay attention to execution quality, some brokers save you pennies but cost you dollars through poor fills.

Options Approval Levels (U.S. Brokers)

Brokers in the U.S. won’t let everyone sell naked calls on day one. Instead, they classify you by approval levels based on your experience, income, and risk tolerance:

- Level 1: Covered calls & protective puts (safest).

- Level 2: Buying calls, puts, and cash-secured puts.

- Level 3: Spreads (defined risk strategies).

- Level 4/5: Naked options and advanced multi-leg strategies.

As a beginner, you will usually start at Level 1 or 2. That’s all you need for the starter strategies we discussed earlier.

Bid-Ask Spread (Your Hidden Cost)

Every option has a bid price (what buyers will pay) and an ask price (what sellers want).

- A wide bid-ask spread = higher hidden costs.

- A tight bid-ask spread = cheaper, more liquid trading.

Example:

- Bid = $4.90, Ask = $5.10 → Tight spread (only $20 round-trip cost).

- Bid = $4.00, Ask = $5.00 → Wide spread ($100 round-trip cost).

Always pay attention to spreads. They can eat into your profits more than commissions.

Why You Should Use Limit Orders

Beginners often use market orders, which buy/sell at the current best price. But in options, this can be dangerous, especially with wide spreads.

- Market Order: Fills instantly, but you may overpay or undersell.

- Limit Order: Lets you set the exact price you want.

Practice Before You Pay: Paper Trading

One of the most common beginner mistakes is rushing straight into live trading without practice.

Options are powerful but also unforgiving. The best way to avoid costly errors is to paper trade first.

Paper trading means simulating trades with virtual money. You are trading in real market conditions, but without risking real capital.

Why Every Beginner Must Paper Trade:

- Learn Mechanics Without Risk:

Options involve multiple moving parts; strikes, expirations, premiums, Greeks, spreads. Mistakes (like buying instead of selling, or confusing a call for a put) can cost thousands in real money. Paper trading eliminates that risk. - Understand Time Decay & Volatility:

Watching how your paper trades react to time and implied volatility teaches you lessons theory alone can’t. - Build Confidence:

Many beginners freeze when placing a live trade. Practicing until it feels routine helps you avoid hesitation later.

Paper trading is like using a flight simulator before flying a real plane. You wouldn’t want your first flight to be with passengers onboard.

How to Use Your Practice Time Effectively

- Start Simple: Place basic trades (buying calls/puts, selling covered calls) to master execution. Use paper trading platforms like thinkorswim or TradingView.

- Test Strategies: Try covered calls, cash-secured puts, and vertical spreads repeatedly. Track your results.

- Experiment With Expirations: Trade weekly vs monthly to see how time decay works.

- Journal Every Trade: Write down the reasoning, expected outcome, and actual result. This habit will save you real money later.

Don’t just treat paper trading like a game. Act as if the money were real. Only then will you develop the discipline to trade successfully.

Paper trading is your safety net. It helps you master execution, build confidence, and understand options behavior; all without risking a dollar.

Step by Step Learning Roadmap for starting your Options Journey

By now, you have built a foundation: what options are, how they are structured, the risks involved, and which beginner strategies are safest.

But trading options is not something you master in a weekend. Its a journey of continuous learning and practice.

Here’s your roadmap to go from curious beginner to confident trader:

Step 1: Master the Basics (Contracts → Pricing → Risks)

- Revisit the essentials regularly: strike prices, expiration, premiums, Greeks, and moneyness (ITM, ATM, OTM).

- Understand how time decay and implied volatility shape every trade.

Print out a simple payoff chart for calls and puts. Keep it by your desk until the logic becomes second nature.

Step 2: Practice Daily with Paper Trading

- Place trades every week in your simulator.

- Focus on covered calls, cash-secured puts, and vertical spreads.

- Track performance, journal your results, and reflect on mistakes.

Treat this like a trading gym. Repetition builds muscle memory.

Step 3: Develop Winning Habits

- Trade Journal: Record your entry/exit, rationale, and lessons learned.

- Risk Management: Never risk more than 1–2% (see top mistakes traders make that loses money) of your account on a single trade.

- Daily Review: Spend 15 minutes each day checking how your positions react to price/time changes.

Tip: Screenshots of your trades help you spot patterns in your decision-making; good and bad.

Step 4: Expand Your Knowledge Base

- Books:

- Options as a Strategic Investment by Lawrence McMillan.

- Trading Options for Dummies by Joe Duarte (great beginner-friendly read).

- Courses: Many YouTube channels and websites offer free courses tailored for beginners.

Be selective. Stick to trusted educators, not hype driven traders flashing Lamborghini ads.

Step 5: Transition to Real Money (Slowly)

- Start with small positions ($100–$300 trades).

- Focus on risk-defined strategies.

- Increase size only after consistent paper-trading success and emotional control.

Your biggest enemy in live trading is not knowledge, it’s emotion. Going slow lets you learn discipline before scaling up.

Summary of the Roadmap

Learn → Practice → Build Habits → Expand Knowledge → Trade Small → Scale Gradually.

Conclusion: From Zero to Confident Beginner

Options may look intimidating at first glance, but as you have seen, they are built on simple principles.

They are just contracts: rights, not obligations; that can be used for speculation, protection, or income.

You now understand:

- How options are structured (strike, expiration, premium).

- The difference between calls & puts.

- The role of time, volatility, and Greeks in pricing.

- The real risks to watch out for (leverage, time decay, volatility crush).

- Safe beginner strategies like covered calls, cash-secured puts, and spreads.

Your next step: Open a paper trading account today and try placing a simple covered call. Watch how it behaves day by day, and you will see these lessons in action.

FAQs: Options Trading for Beginners

What is my maximum possible loss in options trading?

For Option Buyers: Your maximum loss is the premium you paid. If you bought a call for $500, the most you can lose is $500; even if the stock crashes.

For Option Sellers: Risk can be substantial. Naked calls carry unlimited risk, while naked puts can expose you to buying a stock at a much higher price than market value.

What happens if I hold an option until expiration?

If it’s in the money (ITM): It may be exercised (calls = you buy shares, puts = you sell shares).

If it’s out of the money (OTM): It expires worthless, and you lose the premium.

If you don’t want assignment, close your position before expiration.

What is the safest options strategy for a complete beginner?

The two safest beginner strategies are Covered Calls & Cash-Secured Puts. Both strategies are conservative, risk-defined, and excellent for learning.

Disclaimer:

This content is for informational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Examples are hypothetical and exclude fees, taxes, and slippage. We are not affiliated with or endorsed by any company mentioned. If you need personalized advice, consult a registered investment adviser.

Read full Disclaimer.